The use of anonymous enforcers supported with communication has a positive effect on the amount of litter

Mooimakers conducted some research in 2022 on the effect of anonymous litter enforcers on the amount of litter. They also examined whether or not communication about these enforcement actions adds any value. In other words: does this decrease the amount of litter?

The enforcers

Under Flemish Environment Minister Zuhal Demir, some litter enforcement officers started at the Public Waste Agency of Flanders (OVAM). Local authorities can use them free of charge as GAS (municipal administrative sanctions) identifiers. They always work in pairs and can also work at night and at weekends. Several local authorities have already called upon the identifiers.

The research

The research examined the impact of anonymous litter enforcers on the litter present. This may or may not be combined with supporting communications. The cities of Herentals, Geel and Turnhout participated in the research. They are three similar Campine towns with 28,500, 41,000 and 46,000 inhabitants, respectively. Along with city cleaning services, they looked for some locations that were feasible to measure, had litter issues and were sufficiently heavily used.

The use of litter enforcers

The investigation and actual enforcement ran in parallel. The litter enforcers were intensely deployed locally during the weeks when the impact measurements were taking place. Thus, the impetus (the presence of the enforcers) and the hoped-for result (less litter) were as close as possible. Please note that there was no consultation or contact between the investigators and the enforcers. Both functioned independently of one another.

In total, litter enforcers enforced for 78 hours (an average of five hours per day) during the first impact measurement. That is the sum of the number of hours in the three cities. In the second impact measurement, they took slightly less time, with an average of four hours per day. This did not affect the number of interventions at all.

Approach to the measurements

The research included one baseline measurement and two impact measurements in all three cities.

-

The baseline measurement (May 2022)

The baseline measurement captures the condition prior to the deployment of the enforcers. For two weeks, litter was inventoried. In each community, researchers counted the number of pieces on the ground twice a week.

-

The first impact measurement (June 2022)

The first impact measurement took place immediately after the baseline measurement in order to measure the short-term effect. This was also how the researchers minimised the possibility of 'contamination' of the measurement by unforeseen factors in the environment (e.g. the installation of a cigarette receptacle by a catering establishment or the opening of a food retail outlet that brings more litter).

The only meaningful difference between the baseline measurement and the first impact measurement was the presence of the litter enforcers. Because there was no communication between May and June 2022, local residents and passers-by could only be aware of the litter enforcers when they addressed them about their littering behaviour. Or when citizens who interacted with the litter enforcers shared their knowledge with fellow citizens.

-

The second impact measurement (October 2022)

Three months later, the 2nd impact measurement for the medium-term effect followed. This was how they were able to ascertain whether any impact of the initial effect measurement was continuing, growing stronger or in fact diminishing through habituation.

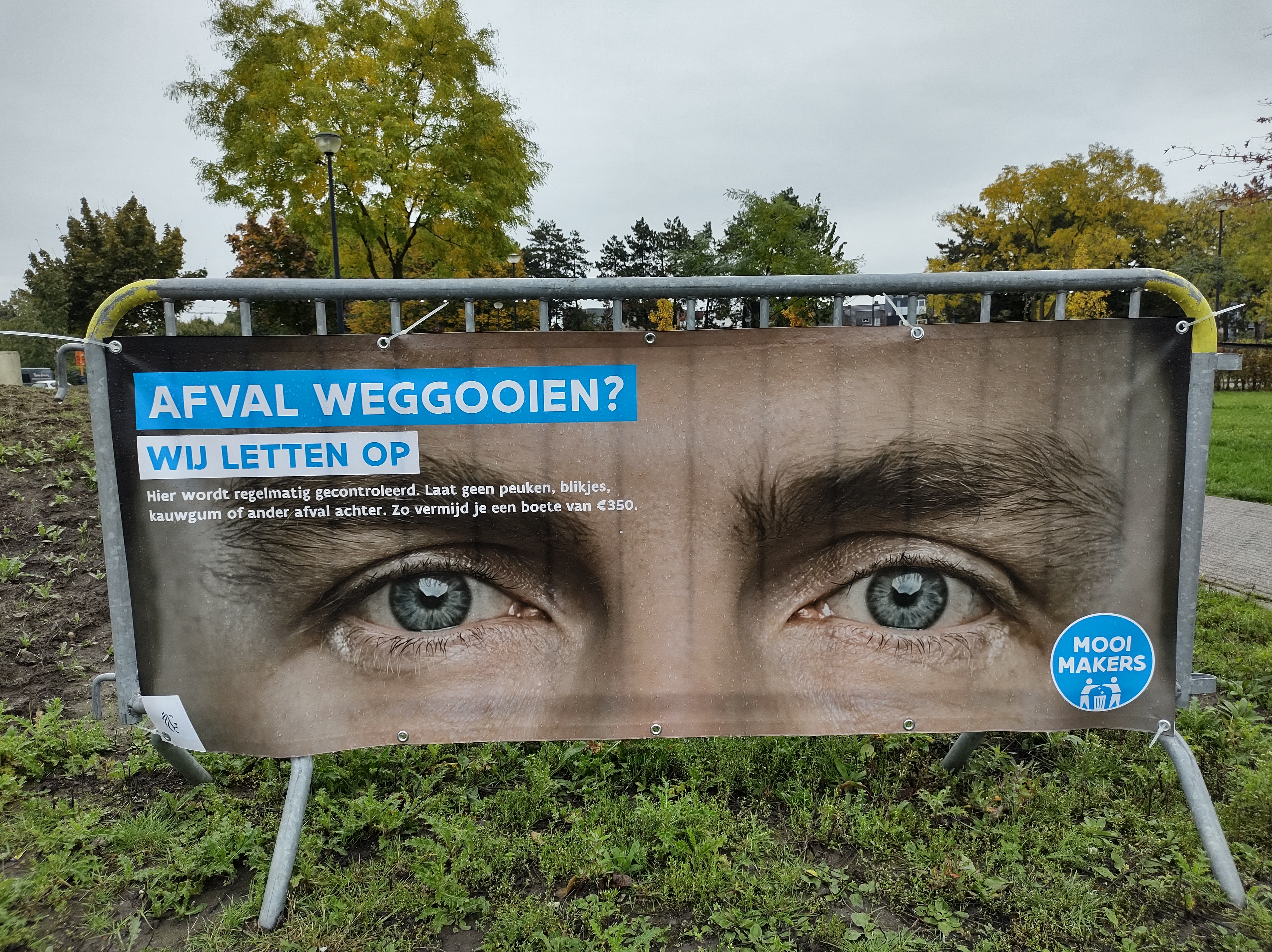

Between the first and second impact measurements, the researchers added 'communication' to the measures. Signs on the streets informed residents of a potential fine if they leave any litter behind. These signs were in the measurement zones or near them. In addition, local authorities informed local residents through online news releases.

In total – from baseline measurement through the second impact measurement – there were 36 counts. Per measurement, 12 counts evenly distributed among the three local authorities. Each series began with what is called a 'sweep': a cleaning of all the litter so that the research literally starts with a clean slate.

The three series of measurements were perfectly comparable. In addition to the same number of completely similar counts on the same days, the research took into account the same times and weather conditions to rule out any atypical cases.

During the measurements, they counted the number of pieces of litter, not the volume. The litter was classified into 12 categories in accordance with the OVAM's most recent cleanliness barometer.

In the second impact measurement, there was an additional record of whether the litter was small or large. The limit was at 3 cm in this regard. Cigarette butts and chewing gum were consequently recorded as 'small'. Cans and dog waste as 'large litter'.

Results

Although the locations were selected for the existence of litter issues, the proportion of pieces of litter varied greatly by location. The location with the greatest pollution is thus struggling with 5 times more litter than the place with the least litter.

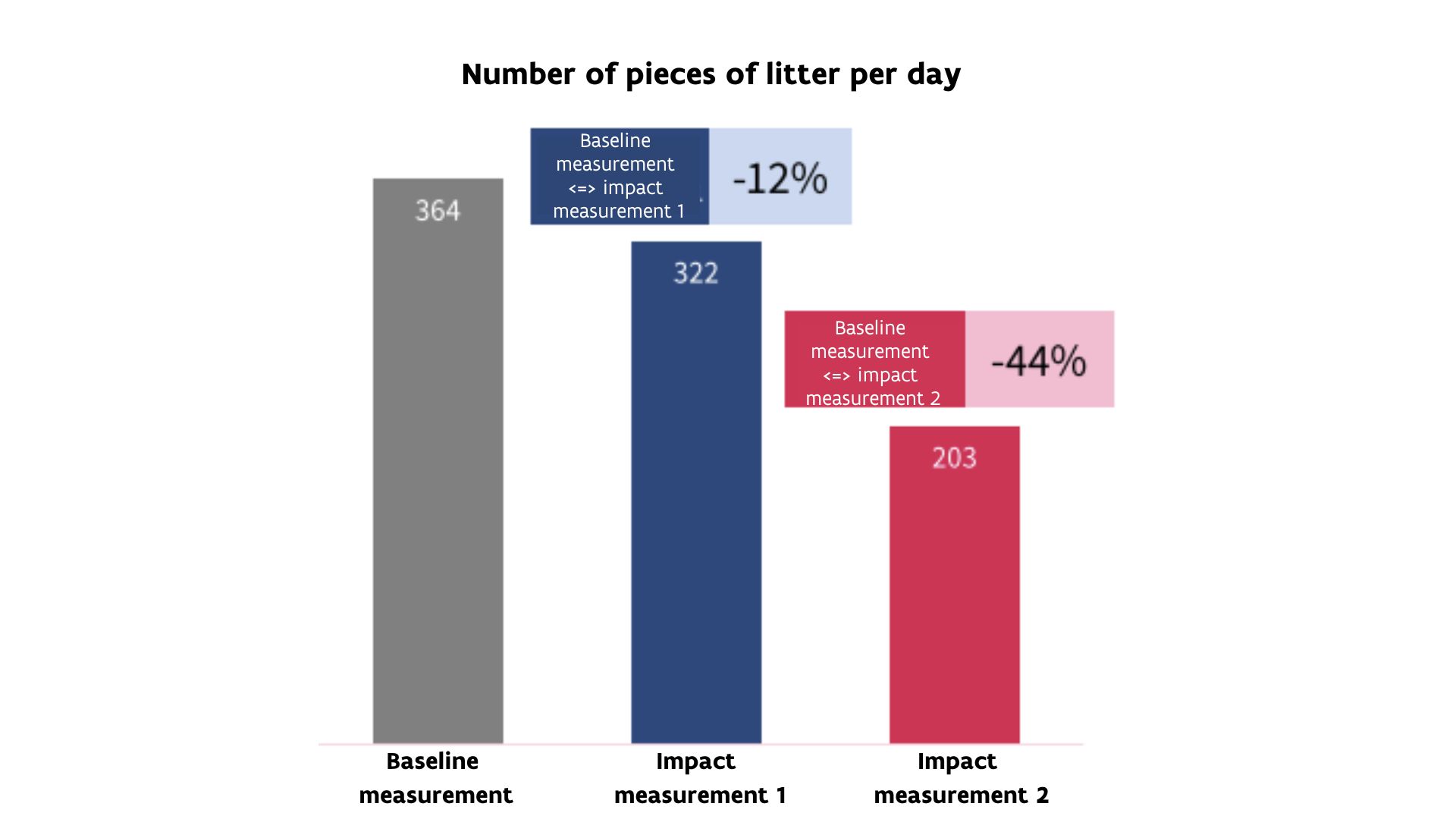

The four counts in the baseline survey inventoried a total of 5,094 pieces of litter. An average of 364 new pieces of litter per day. Per location (which averaged 400 m2), this is equivalent to almost 1 piece of litter (0.9) per 10 m2 per day. As much as 52% of all the litter in the baseline survey was cigarette butts. In addition, mainly paper and cardboard (14%), plastic (10%) and food packaging (9%) were found.

When the litter enforcers record catches, they note what type of litter people leave behind. This is sub-divided into seven categories. More than 90% of the cases involve smokers throwing their cigarette butts on the ground.

First impact measurement results: a non-significant decrease in litter volume

The first impact measurement identified the effect of the presence of enforcers on the creation of litter. A modest decline of 12% was recorded. Statistically, this decline is non-significant. In other words, it is not pronounced enough to conclude that the use of enforcers reduces littering. Specifically with cigarette butts, the same observation was made, namely no significant decrease (6%) in the first impact measurement

Second impact measurement results: a remarkable decrease in the volume of litter.

During the second impact measurement, communication supported the efforts of the litter officers. Given that the rest of the variables (frequency of presence of litter enforcers, number of visual inspections and civil reports, lack of spatial changes, etc.) remained stable, we can conclude that the combination of the use of the litter enforcers and additional supporting communication efforts have a great effect on the creation of litter. A drop of as much as 44% was recorded. In fact, cigarette butts present dropped by a whopping 47%. 80% of the litter was smaller than 3 cm. This is an overwhelming majority.

Conclusion

On average, the number of pieces of litter decreased by 44 percent in the second impact measurement compared to the baseline measurement. That marked decline continues at each of the 10 locations. Thus, we can say with certainty that litter enforcers have a positive effect on litter creation in the event that their action is supported by communication. In other words, communication has great added value.